The untold story of SSG operation at APS

(Based on background interviews with the commandos who conducted the APS operation and security officials)

It’s a bright, sunny, winter morning. The mist has cleared and everything is alive with the warmth of the sun after a long, freezing night. But a chill still lingers in the air. Something is amiss. The air is heavy with an eerie sense of foreboding.

At the Ghazi Base, the headquarters of the Pakistan Army’s elite Special Services Group, commandos are competing for the title of best marksman. A message is radioed for Zarrar Company, which specialises in anti-terrorist and heliborne operations. There is a situation in Peshawar. And they have to fly. At once. No time for procedures. No mission brief, no recon, nothing. Just pack up and fly.

Normally, the SSG needs at least one-and-a-half hour to prepare for a mission. But today, they are battle-ready within 20 minutes and board the helicopters. They are going for a mission that will turn out to be arguably the toughest of their lives. Never before in the history of the SSG has an assault team readied for a mission at such short notice.

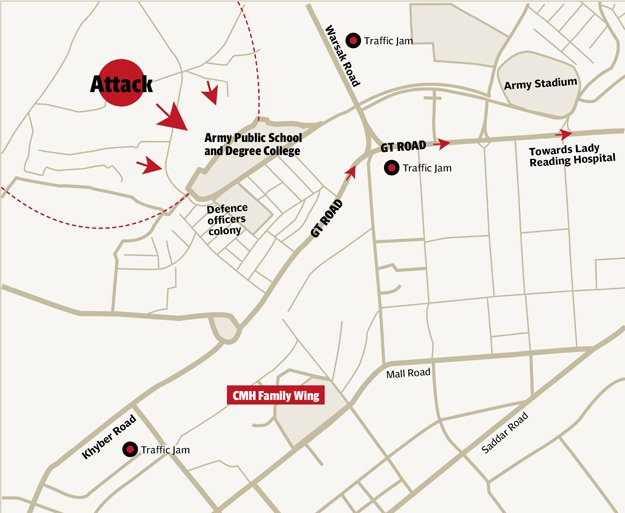

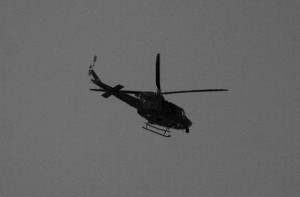

The commandos still don’t know what awaits them in Peshawar as five Mi17 helicopters carrying them lift off. En route they are informed about the mission: terrorists have attacked the Army Public School. Nearly a thousand students are registered in the military-run institute and a massacre is feared. Nearly 40 minutes later, the Mi17s land at Peshawar’s Army Stadium and the commandos are driven straight to the scene of action.

Outside the school, it is sheer chaos, utter panic. Wailing ambulances ferry the casualties; military men rush rescued schoolchildren to safety; distraught parents frantically search for their children, jostling to break the security cordon. Sporadically, gunshots ring out inside and small explosions go off.

It’s a race against the clock. Every moment is precious. Every second can mean life — or death. This isn’t a hostage situation; the terrorists are methodically killing everyone, not even sparing those as young as five. After a quick, short briefing, the operation commander decides to launch the first assault team. “Who will volunteer?” the commander asks. Everyone steps forward.

The first assault team is quickly assembled. There is no time for contemplative strategy. As a commando who took part in the assault would later say, “It was one of the toughest operations for us in many ways.” They would have to fall back on their core instincts, honed by specialised training.

Four commandos go inside and cordon off the nursery section. Dozens of toddlers are rescued. As they move to secure other classrooms, a piece of glass cracks under the boots of one commando. Three terrorists inside a classroom are alerted. They fire a barrage of gunshots. A hand grenade follows.

The grenade lands hardly five metres away from the commandos. Luckily, it doesn’t go off. As the commandos take cover, another grenade is hurled. It explodes around 15 metres from them. Some sustain shrapnel wounds. They do not fire back, fearing there will be children inside.

“There was little time for calculating our moves,” the commando would later reflect. “Whatever had to be done had to be done quickly. The terrorists were rampaging through the compound and killing whoever they found. We could not fire back at the terrorists freely because we wanted to ensure no child was hit by our bullets.”

A second assault team springs into action. And they barge straight into the room from where they received fire. It is a stun action. The terrorists loaded with AK-47 assault rifles, hand grenades and suicide vests fire a hail of gunshots but miss. In a lightening reflex-action the commandos strike back. Two terrorists lie dead on the ground, a third is hit and the explosives strapped to his body goes off; perhaps, by the impact of the bullets.

“In hostage situations, a counter assault is meticulously planned and carefully executed,†another commando would later state. “But we didn’t have much time for planning as the terrorists were on a killing spree. They did not plan on taking hostages.”

Hearing the explosion, a fourth terrorist runs towards the classroom. He blows himself up on the veranda. “He was looking skyward and his back was towards the assault team. One commando was hit by shrapnel and martyred,” the commando would later recall. It is the first, and turns out to be the only, fatality Zarrar Company sustained in the entire operation.

Two more terrorists emerge from another block. They fire at the commandos but a third assault team covering them engages and takes them down before they detonate the explosives strapped to their bodies. As the commandoes move forward, they hear screams and cries of children from a classroom. Going in from the main door can be risky. They break the exhaust fan of the classroom and get inside with the help of a scaling ladder. Dozens of children are rescued.

The assault teams are unsure how many more attackers are still on the loose in the sprawling compound. The sun is setting. Concerns for the safety of survivors grow. The terrorists can take advantage of darkness and kill more. Looking back, the commando would highlight this disparity of information. “We had little information about the building, like the number of rooms, where they were located, and so on. The terrorists, on the other hand, had done proper recce before the attack.”

A fourth assault team is launched. And they all begin stacking, a term used in the military for cordoning off areas to restrict the enemy’s movement. They move block to block to secure the areas and deny the terrorists ease of movement.

Two terrorists have moved to the administration block. The commandos pin them down in the Principal’s office. One is shot dead, but the second triggers the charge. The body of the Principal, Tahira Qazi, would later be found in the bushes outside her office with a single shot to the front of her head. The body is believed to have been thrown out of the office by the impact of the suicide blast.

The combat has now lasted nearly four hours. Hundreds of pupils have been rescued. But the SSG teams want to comb the entire premises to make sure all the terrorists have been sent to hell. It takes them a few more hours to declare the premises clear for a subsequent sweeping operation. There are fears that the terrorists might have rigged the building with improvised explosive devices.

While the clearance operation is ongoing, information is radioed to the commandoes about more than a dozen staff hiding in a washroom. Throughout the bloody rampage they have been in contact with military officials outside the school and told them about their whereabouts and asked for help. In the end, they are rescued by the commandos.

Nine hours after the cataclysmic siege began the military secures the entire compound. The scenes are unspeakable. The air is filled with fresh gunpowder and smoke. Almost every wall is pockmarked with bullets or torn off by explosives. The blackened rooms, the lawns and the verandas are scattered with the dead and the injured.

Most of the casualties happened before the SSG commandos mounted the assault. After sneaking into the school, the terrorists, donning military fatigues, went straight for the auditorium where a first aid training session was in progress. It was here the bulk of the carnage played out. Nearly 100 people, mostly students, were massacred. Those who found ways to escape were chased and hunted down on the lawns and on the veranda. However, the quick action of the SSG commandos saved hundreds of lives because the terrorists planned to hold off for as long as they could and spill as much blood as they could.

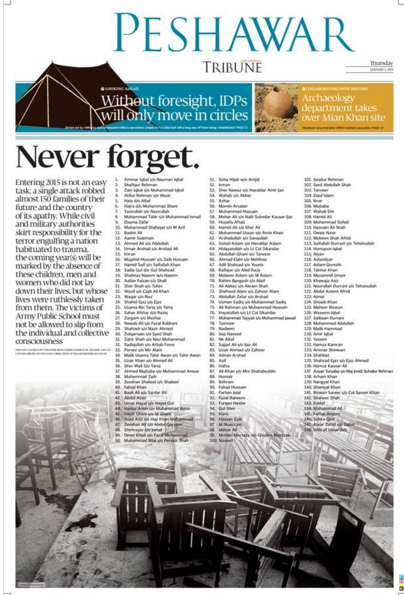

Piles of bullet-riddled bodies of children. Blood-stained uniforms and books. Agonizing screams and moans of the injured youth. Frantic cries for help. Pure, primal desperation. These scenes were enough to shatter the composure of SSG commandos who have through their careers seen blood and gore in all its varieties. “When I came back home and met my children,” says another commando now, almost a year on from the attack, “I thought of the parents who lost theirs in the APS attack and I choked on tears. Only a parent can feel the pain of losing a child.”

The untold story of SSG operation at APS

The untold story of SSG operation at APS

Seven hours of terror in Peshawar

Seven hours of terror in Peshawar

Rescue workers recall ‘blood and bullets’ inside APS

Rescue workers recall ‘blood and bullets’ inside APS

Covering the attack

Covering the attack